Which way, juniors?

Which way, juniors?

The 'unseen' in the software industry

Which way forward? The critical decision point facing junior developers in the AI era

Over the past few months I have noticed that there is a special kind of buzz in the air that is difficult to define. It looks to me like a permanent change that is taking place, almost like a shapeless progress bar installing something within the structure of the IT world. Some of us are aware of it, but few of us are willing to debate it sincerely nor even willing to touch its "conclusions" button with a 10 foot pole.

But I'll try to do the very thing people are hesitant to do, which is describing the problem and perhaps dare to offer some solutions.

The Unseen Problem: Bastiat's Window

In 1850, the French economist Frédéric Bastiat told a simple story: A boy breaks a shopkeeper's window. Onlookers console the shopkeeper by pointing out that the broken window is good for the economy—after all, the glazier will earn money fixing it, which he'll then spend elsewhere, creating a ripple of economic activity. But this reasoning, Bastiat argued, commits a fatal error: it only considers what is seen—the glazier's new income—while ignoring what is unseen—what the shopkeeper would have done with that money had the window not been broken. Perhaps he would have bought new shoes, benefiting the cobbler. The broken window doesn't create prosperity; it merely redirects it while destroying value.

This distinction between the seen and the unseen is perhaps economics' most powerful lens for understanding unintended consequences. What we're witnessing in the software industry today is our generation's version of the broken window fallacy. The seen: companies saving money by not hiring junior developers, AI increasing immediate productivity, leaner teams producing more output per engineer. The unseen: the hollowing out of the talent pipeline, the coming shortage of experienced mid-level developers, an entire generation's economic potential being redirected away from their field of study, and the long-term erosion of innovation that happens when fresh perspectives stop entering the industry.

Just as the broken window's cost wasn't visible in the glazier's earnings, the true cost of abandoning junior developer hiring won't show up in this quarter's balance sheet. But it's real, it's accumulating, and eventually it will shatter something far more expensive than a window.

The anecdotal effects I've felt personally through the amount of calls, personal messages, and appeals for guidance from recent graduates who stepped off their faculty benches onto what they imagined would be a welcoming professional world—one where their computer science degrees would unlock doors, where their passion for technology would be rewarded with opportunity.

Their one focus and scope: a job. But the doors they knocked on remained firmly closed.

The silent epidemic: rejection emails that never acknowledge the human cost

The Job Problem

Ah yes, The Job. Our parents put a significant emphasis of importance around this one word, and even us as children were conditioned indirectly to perceive this as something important.

This indirect influence from our parents pushed our curiosity to understand the first questions about the economic relationships between people. What does it mean to be an employee? How does it feel to get paid for something you are doing? These aren't abstract academic questions—they're deeply personal inquiries about how we fit into the economic fabric of society. The Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises captured this perfectly when he wrote: "Economics must not be relegated to classrooms and statistical offices and must not be left to esoteric circles. It is the philosophy of human life and action and concerns everybody and everything." In other words, understanding economics isn't optional when you're trying to navigate a job market—it's essential for making sense of what you're experiencing.

So when the recently graduated students called me with their questions, they weren't asking about economics—they were voicing their fears:

- "What are we going to do? Nobody is hiring."

- "I've been to 12 interviews but nobody is contacting me back, not even to tell me they've picked someone else."

- "I'm looking for a year now without success. What am I doing wrong?"

Trying to ponder this current whispering from a position of ignorance would translate into something like: "We have a JOB PROBLEM! There are not enough jobs!" But this framing, while emotionally valid, misses the deeper economic reality at play.

I, myself was a victim of this thinking when searching for my first IT job back in the day, applying to tens of job postings all over the internet and even physically going to those companies and giving them my CV. Those days were pretty hard on my psyche, because although I was even willing to accumulate experience in unpaid roles, there were no positions available anywhere.

I have a soft spot for those that are going through what I went through, so do forgive me if this article seems opinionated or too subjective.

What's Actually Happening

Most people know that this job problem is rooted in supply versus demand balance: the supply of available software engineers is much too high for the demand that exists. Statistics bear this out dramatically: entry-level tech hiring decreased 25% year-over-year in 2024, with entry-level postings dropping a staggering 60% between 2022 and 2024.

Data reflects industry-wide trends in entry-level software engineering positions (2022-2024)

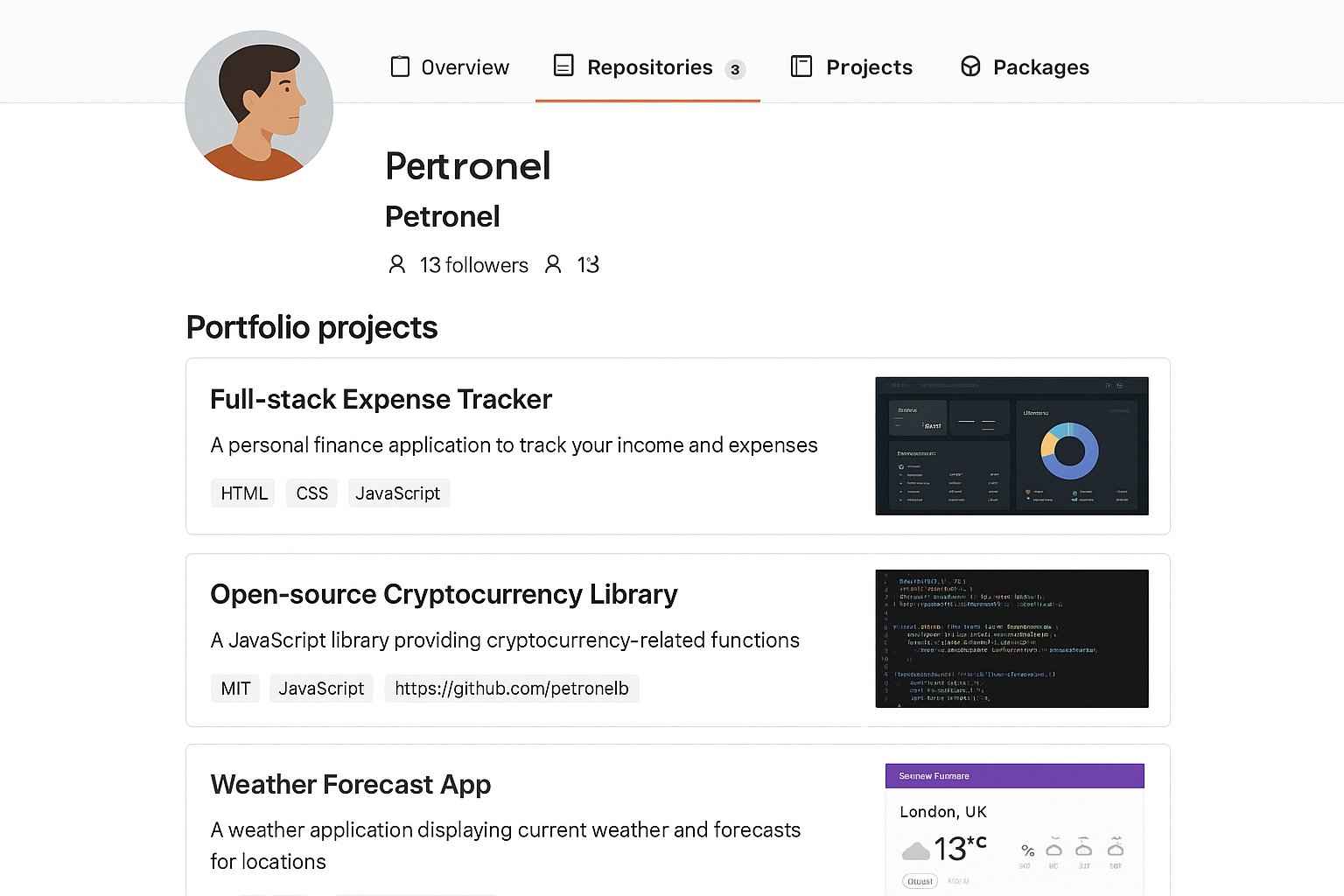

Let me introduce you to a composite character—let's call him Petronel. He's 24, recently graduated from a decent technical university in Romania with a degree in Computer Science. His grades were solid, not exceptional. He did a few small projects during university—a todo app, a basic e-commerce site, a weather dashboard. He learned Java in school, taught himself some JavaScript and React on the side. On paper, he's exactly the kind of candidate that would have been snapped up by any mid-sized tech company in 2021.

It's now November 2025. Petronel has been looking for his first developer job for 14 months. He's applied to over 200 positions. He's had seven interviews, all of which ended with polite rejections or, more often, silence. The few pieces of feedback he's received have been contradictory: "You need more experience" (but how do I get experience without a job?), "Your projects are too basic" (they're exactly what the online tutorials taught), "We're looking for someone more senior" (the posting said entry-level).

Petronel is now working as a delivery driver for a food app, making barely enough to cover rent in a shared apartment. His confidence is eroding. He still codes sometimes in the evenings, but increasingly he wonders if he wasted four years on a degree that's led nowhere. He's fallen into a gap between education and employment from which escape seems increasingly impossible.

The reality gap: From coding aspirations to economic survival

The story you just read is a composite, but it's playing out in thousands of variations right now. And the consequences extend far beyond individual disappointment—they have measurable, long-term economic implications.

The Economic Penalty of Career Entry Delays

Research on career trajectories consistently shows that delays in entering your chosen field have compounding negative effects. Studies indicate that taking more than one year from graduation to first career-relevant employment correlates with a roughly 20% reduction in lifetime earnings. This isn't just about the lost salary during that year—it's about the trajectory.

The mechanism is straightforward: missing that first year means you're not accumulating experience, not receiving mentorship, not building professional networks, not learning the soft skills of workplace collaboration. When you finally do enter the field, you're competing with people who have a year's head start. Over a 40-year career, that initial gap compounds through slower promotions, smaller raises, and fewer opportunities for advancement.

For someone in Petronel's position—14 months and counting—the penalty is already significant and growing. If this pattern affects an entire cohort of would-be developers, we're looking at a generational wealth transfer away from young technical professionals toward those who entered the field before the AI disruption.

The Underemployment Trap

Research shows that entry-level graduates who fail to enter their field of study within the first 18 months are approximately 60% more likely to end up underemployed in the medium term—meaning they're working in roles that don't require their education or skills.

Not long ago, you could graduate with an adjacent degree, learn some programming basics, and transition into a developer role. That accessibility was a feature, not a bug—it meant diverse perspectives, second-chance careers, and upward mobility for people from non-traditional backgrounds.

But nowadays, the career path pattern is irrevocably altered. Many graduates with software engineering degrees will diverge into other low-barrier-to-entry activities like courier jobs, rideshare driving, or hospitality. And once you're in that underemployment trap, escape becomes exponentially harder. The longer your resume shows "Uber driver" instead of "Junior Developer," the harder it is to convince a hiring manager to take a chance on you.

Before and After: The Career Path Transformation

World Before AI (2015-2022): Go to university, barely graduate with a passing GPA, look for a job for a maximum timeline of 1-3 months, get hired with €800-1,000/month starting salary. Beat Romania's inflation rate with a 10-15% yearly increase. Do opportunistic job-hopping every 2-3 years with 30-50% salary increases each time. By your late 20s, you're making €3,000-4,000/month, living comfortably, maybe buying property.

World After AI (2024 onwards): Complete a rigorous CS degree with genuinely good grades. Build a substantial portfolio of complex projects that demonstrate not just coding ability but system design thinking and AI integration skills. Expect to spend 6-18 months searching for that first role. When you finally land a position, it will likely be contract-based or probationary, with intense scrutiny during a trial period. Starting salary might be €1,200-1,500/month—but adjusted for inflation, it represents less purchasing power than the 2019 equivalent.

Career progression will be slower and less predictable. The clear junior-to-mid-to-senior ladder has been replaced by a steeper, narrower staircase where many get stuck at the bottom rungs. Job-hopping is riskier. The 30-50% salary jumps of the past become 10-15% increments. By your late 20s, if you successfully navigate this treacherous landscape, you might be making €2,500-3,000/month—respectable, but a harder road to the same destination, with far more casualties along the way.

Career Path Transformation: Then vs Now

The fundamental shift in career trajectory expectations for software developers

The Future Supply Problem

Here's the crisis nobody's talking about: in about 3-5 years, there will be a massive shortage of mid-level developers. Not because there aren't people with 3-5 years of experience, but because there won't be people with 3-5 years of quality experience.

Think about it: if we stop hiring juniors in 2024-2025, who becomes the mid-level developers of 2028-2029? You can't promote what you didn't hire. Companies will panic. They'll try to hire mid-levels and find the market barren. Many will turn to offshore outsourcing at scale, further hollowing out local tech ecosystems.

The decision to not hire juniors today looks rational on this quarter's balance sheet. The consequence—a critical talent shortage in 3-5 years—is invisible in current financial models. But it's as predictable as any economic cycle.

The University Response (or Lack Thereof)

So what are Romanian universities doing about this transformation? The answer, unfortunately, is: not nearly enough.

To their credit, some institutions are making moves. Politehnica București launched a Master's program in Artificial Intelligence, and the university recently partnered to build Romania's first AI Factory—infrastructure for AI research and development. Babeș-Bolyai University formed a strategic partnership with Microsoft Romania to organize courses in cloud computing, AI, Big Data, and cybersecurity. These are positive steps.

But here's what these initiatives miss: they're bolting AI education onto existing structures rather than fundamentally rethinking what computer science education needs to be in this new era. A master's program in AI is valuable, but what about the thousands of undergraduates in traditional CS programs learning the same curriculum that was designed for a job market that no longer exists? What about the disconnect between what's being taught and what employers now expect from entry-level candidates?

The real issue is the value proposition universities are offering students. "Get a computer science degree and you'll get a good job" was true for decades—it's what drew students like Petronel to spend four years and considerable money on their education. That implicit promise has broken, yet universities haven't adjusted their messaging or their offerings to reflect the new reality. Students are graduating with "outdated knowledge" into a market that has fundamentally shifted beneath their feet, and many are understandably feeling betrayed by an educational system that didn't prepare them for what they'd actually face.

Meanwhile, 64.6% of Romanians believe the state should actively support professional training in AI-related fields, particularly among young people aged 18-29, who are calling for a national strategy that encourages innovation and specialist training. The demand for change is clear—but institutional response remains slow, bureaucratic, and insufficient to the scale of disruption students are experiencing as they enter the workforce.

Facing the Inevitable Change

In the COVID era when recruiters were begging you to apply for a job and employees were posting "Day in the life" videos where half their day was spent drinking lattes, as a future developer you were promised a world of milk and honey. Remote work forever, unlimited PTO, six-figure salaries for junior roles.

That was an aberration—a brief moment of irrational exuberance. It felt normal while it lasted, but it was never sustainable.

I'm not going to lie to you: the breed of what a junior programmer represented until 2022 will disappear entirely in the following years. That role—the person who primarily writes boilerplate, implements simple features from detailed specs, and learns on the job at the company's expense—is economically unviable in a world where AI can do those tasks faster and cheaper.

The amount of hand-holding will decrease. The tolerance for entry-level costs will decrease. The expectation that you'll spend your first year mostly learning rather than contributing will evaporate. This is harsh, but it's the reality we must confront honestly if we're to navigate it successfully.

Solutions: Advice for Junior Programmers

If you're a junior developer or aspiring to be one, the previous sections might have been demoralizing. That's not my intention. My intention is to provide a clear-eyed assessment of the situation so you can strategize effectively. And there are strategies—this is challenging, not impossible.

Navigating the new landscape with strategic preparation and AI fluency

1. Code Yourself, Learn to Fail

Do most of the coding yourself. Constantly grease your synapses by learning functions, code syntax, styling, and force yourself to wing it sometimes, even if the result is disastrous. You are obligated to fail as much as possible at this point. Failure means learning.

When you're learning, the struggle is the point. The hour you spend debugging a seg fault, the frustration of CSS that won't cooperate, the confusion about why your API isn't returning the right data—these experiences build intuition in a way that instant AI-generated solutions never will.

There's a concept in learning theory called "desirable difficulty"—tasks should be hard enough to require effort, because that effort strengthens learning. If everything is easy (because AI does it for you), you don't build the neural pathways that constitute genuine skill.

2. Use AI Strategically, Not as a Crutch

Your AI usage can be more detrimental than useful at this stage if you're not careful. Here's how to use it productively:

Use it for short, specific tasks—never for full features. Don't prompt: "Build me a user authentication system." Instead prompt: "Explain how JWT token expiration works" or "Write a function to validate email format with regex."

Take time to understand the generated code deeply. If the AI writes 50 lines of code, take it line by line. Ask questions and make notes on the snippets you don't understand. Alter the code intentionally until it generates a different response or breaks, and watch your brain analyze what happened. Repeat the process until you can explain what the code does in your own words.

Use AI as a mentor substitute, but actively. AI can partially fill that gap—but only if you use it correctly. Don't just accept the code and move on. Engage with it: "Why did you use this approach instead of that one?" "What are the trade-offs here?" "What could go wrong with this implementation?"

Break the temptation of vibe coding. "Vibe coding" is the temptation to just prompt for what you want, get plausible-looking code, and ship it without understanding. It's the low-hanging fruit that's poisonous. Resist it ferociously. Every time you vibe code, you're sacrificing learning for short-term convenience.

3. Don't Lead with AI in Interviews

Do not bring up AI tools in an interview unless explicitly asked. Many hiring managers worry that junior candidates who emphasize AI use are signaling that they can't code without it. "I rely heavily on ChatGPT for coding" translates in many ears to "I don't actually know how to program."

If asked about AI tools directly, be honest but emphasize fundamentals: "I use AI tools like Claude or ChatGPT strategically for specific tasks—researching libraries, generating boilerplate, getting unstuck on syntax. But I make sure I understand everything they generate before using it, and I regularly code without them to maintain my fundamentals." This signals that AI is a tool you control, not a crutch you depend on.

4. Dramatically Increase Your Soft Skills

This is huge and often overlooked. Since the tolerance for difficult personalities has lowered, being agreeable and a genuine team player is still a hard-to-find skill in today's job market.

AI can't replicate: clear communication, collaborative problem-solving, the ability to give and receive feedback gracefully, emotional intelligence in team dynamics, stakeholder management, explaining technical concepts to non-technical people.

If you're equally skilled technically but significantly better interpersonally than other candidates, you'll win the job. Invest in communication skills, practice explaining your work clearly, learn to work effectively in teams, become someone people want to work with.

5. Renounce Technology Stack Tribalism

The old tendency to be sticky with your technology stack is increasingly a liability. The "I'm a Java developer" or "I only do React" mindset limits your options in a tightening market.

If you fancy Java since university, be open to diving into some frontend frameworks like Angular or React. Learn the basics of systems design even at a beginner level. Take an interest in what it means to construct a project from head to toe—not just the coding, but the architecture decisions, deployment strategies, monitoring and observability, security considerations.

This breadth makes you more hireable (because you can fill multiple roles) and more valuable (because you can see the bigger picture). In a market that's valuing generalists who can contribute across the stack, T-shaped skills—deep in one area but competent across many—are golden.

6. Stay Connected to the AI World

Remain connected to what's going on in the AI world even if you don't completely dive into it. Read the major announcements, understand the capabilities of the leading models, be aware of how the tools are evolving.

You don't need to become an AI specialist, but you need to understand the landscape well enough to have intelligent conversations about it and to recognize opportunities where AI can add value.

AI is an incredible tool—you now have a universal tutor that you can use and profit more from the learning process than any previous generation of junior programmers before you. Take advantage of that. But do so strategically, always prioritizing your own learning and skill development over short-term productivity.

7. Build Real Projects That Demonstrate Value

Your portfolio needs to go beyond tutorial projects. Employers have seen thousands of todo apps and weather dashboards. You need projects that demonstrate:

- System design thinking: Projects with multiple components working together, not just single-page applications

- Production considerations: Authentication, error handling, logging, testing, deployment

- Business value: Solve a real problem, even if it's small. Build something people could actually use.

Contribute to open source projects if you can—even documentation improvements or small bug fixes count. They demonstrate that you can work with existing codebases, follow contribution guidelines, and collaborate with others.

The Future

Portfolio excellence: Real projects that demonstrate technical depth and business value

Let's talk about what happens if current trends continue. What does the software development landscape look like in 5-10 years?

What a Junior Developer Will Mean in 2035

Following the current trend and if I was to make a forecast about what a junior developer will be in 10 years, it will be significantly different from today. Software engineering is not dying, but for juniors expecting to do repetitive CRUD work, building simple APIs, or creating documentation, it will be a brutal market ahead.

The requirements to succeed as a software engineer in this future market will include:

- Understanding the product direction and customer value: Not just implementing features, but understanding why they matter

- Focusing on building things that drive revenue: Business impact becomes a core technical skill

- Shipping reliably: Ownership of features from conception through maintenance

- Communicating clearly: With technical and non-technical stakeholders, in writing and verbally

- Systems thinking: Not just being a code owner, but understanding how your component fits into the larger system

The "junior" of 2035 will likely have skills equivalent to what we'd call a "mid-level" developer in 2023. The bar for entry will be higher, the apprenticeship period shorter and more intense, and the expectations of business impact will be immediate rather than delayed.

The future workspace: AI-augmented development in 2035

Inevitable Efficiency Increases

Efficiency genuinely will increase. We've seen this pattern repeatedly through technological history. In the early days of web development, you wrote HTML in Notepad, uploaded files via FTP, and debugged by viewing source in the browser. The progression to modern IDEs, version control, automated testing, CI/CD pipelines—each step made developers vastly more productive.

AI is the next step in that progression. The question isn't whether a developer in 2030 will be more productive than a developer in 2020—they will be, dramatically so. The question is how many such developers will be needed. Will we need 10 engineers to "screw a lightbulb" in the future? No—the efficiency will be so great that we'll need only 2-3 engineers to accomplish what previously required 10.

The Rise of New AI-Oriented Positions

There will be new positions invented—AI-oriented roles that don't quite exist yet in standardized form:

- AI Code Auditors: Specialists who review AI-generated code for security, quality, and architectural consistency

- Prompt Engineers: Not just people who can write good prompts, but those who can design prompting strategies, build prompt libraries, and optimize AI integration workflows

- AI-Human Integration Specialists: People who figure out optimal divisions of labor between AI and human developers

- Synthetic Codebase Architects: Developers who specialize in managing and maintaining largely AI-generated codebases

These roles will absorb some displaced developers, but not all. They'll require more expertise than entry-level, continuing the trend of difficulty breaking into the field.

Conclusion

Change is upon us whether we like it or not. There's a conversation I saved some time ago—an AI-related discussion in a forum somewhere—that marked me. It encapsulates both the fear and the reality of this moment:

Human expertise amplified by AI

John: "One key difference people ignore: humans learn from their mistakes. Senior engineers make errors, sure, but they remember them, build intuition, and improve over time. LLMs don't—they repeat hallucinations, forget constraints, and need constant human oversight. That's why no amount of hype changes the fact that real engineering still depends on skilled humans."

Nick: "This is true... until it isn't. In biology, the protein folding Nobel Prize that was solved through AI—no human would be able to manually predict something that complex. If that kind of technology is able to solve a 50-year-old challenge that multiple geniuses couldn't solve on their own, I'm pretty sure our jobs as software engineers is not that difficult to streamline and automate with AI. This technology will only get better with time and definitely would surpass us if developed correctly. I'm on the side of humans, but thinking that AI can never improve from the state it is today is also pretty silly."

So which way, juniors? John and Nick each hold a fragment of truth—human intuition remains invaluable, yet betting against AI's trajectory has been historically unwise. The path isn't about choosing sides in this debate; it's about recognizing that software engineering isn't disappearing, it's evolving. The developers who thrive will combine deep technical fundamentals with AI fluency, strategic thinking with adaptability, and code competence with genuine human skills that machines can't replicate.

The easy era is over, but forward remains the only viable direction—and perhaps that challenge is precisely what will forge a more capable, more valuable generation of engineers.